Sequential Monte Carlo¶

Introduction¶

Arguably the core of QInfer, the qinfer.smc module implements the

sequential Monte Carlo algorithm in a flexible and robust manner. At its most

basic, using QInfer’s SMC implementation consists of specifying a model, a

prior, and a number of SMC particles to use.

The main component of QInfer’s SMC support is the SMCUpdater class,

which performs Bayesian updates on a given prior in response to new data.

In doing so, SMCUpdater will also ensure that the posterior particles

are properly resampled. For more details on the SMC algorithm as implemented

by QInfer, please see [GFWC12].

Using SMCUpdater¶

Creating and Configuring Updaters¶

The most straightfoward way of creating an SMCUpdater instance is to

provide a model, a number of SMC particles and a prior distribution to choose

those particles from. Using the example of a SimplePrecessionModel,

and a uniform prior \(\omega \sim \text{Uni}(0, 1)\):

>>> from qinfer import SMCUpdater, UniformDistribution, SimplePrecessionModel

>>> model = SimplePrecessionModel()

>>> prior = UniformDistribution([0, 1])

>>> updater = SMCUpdater(model, 1000, prior)

Updating from Data¶

Once an updater has been created, one can then use it to update the prior distribution to a posterior conditioned on experimental data. For example,

>>> true_model = prior.sample()

>>> experiment = np.array([12.1], dtype=model.expparams_dtype)

>>> outcome = model.simulate_experiment(true_model, experiment)

>>> updater.update(outcome, experiment)

Drawing Posterior Samples and Estimates¶

Since SMCUpdater inherits from Distribution,

it can be sampled in the same way described in Representing Probability Distributions.

>>> posterior_samples = updater.sample(n=100)

>>> posterior_samples.shape == (100, 1)

True

More commonly, however, one will want to calculate estimates such as

\(\hat{\vec{x}} = \mathbb{E}_{\vec{x}|\text{data}}[\vec{x}]\). These

estimates are given methods such as est_mean() and

est_covariance_mtx().

>>> est = updater.est_mean()

>>> print(est)

[ 0.53147953]

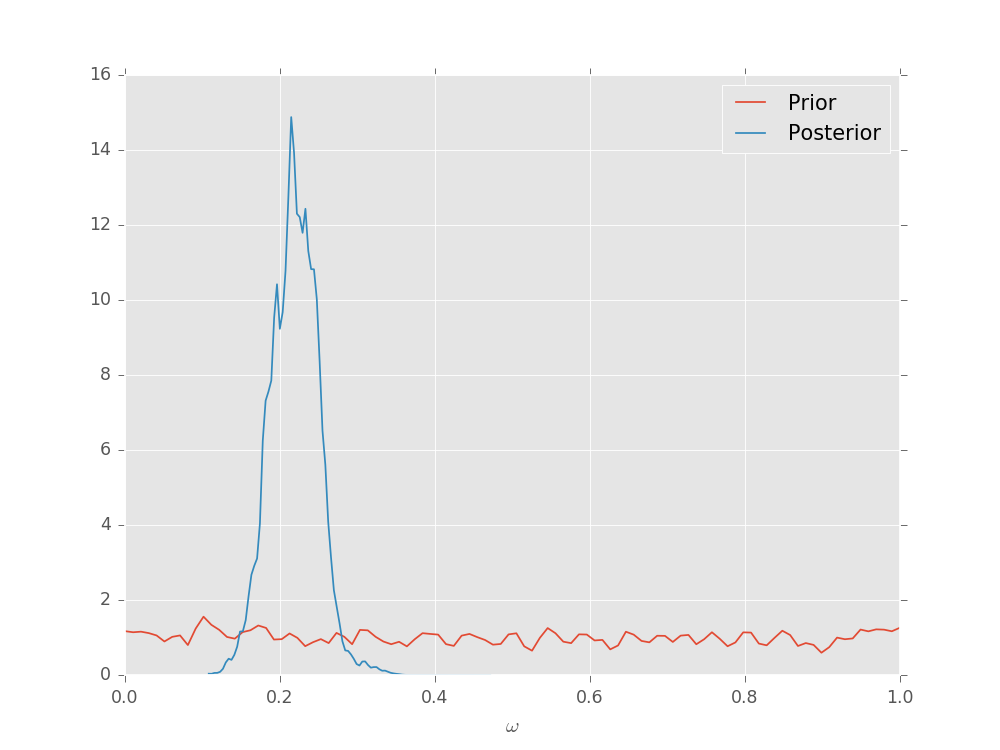

Plotting Posterior Distributions¶

The SMCUpdater also provides tools for producing plots to

describe the updated posterior. For instance, the

plot_posterior_marginal() method uses kernel

density estimation

to plot the marginal over all but a single parameter over the posterior.

prior = UniformDistribution([0, 1])

model = SimplePrecessionModel()

updater = SMCUpdater(model, 2000, prior)

# Plot according to the initial prior.

updater.plot_posterior_marginal()

# Simulate 50 different measurements and use

# them to update.

true = prior.sample()

heuristic = ExpSparseHeuristic(updater)

for idx_exp in range(25):

expparams = heuristic()

datum = model.simulate_experiment(true, expparams)

updater.update(datum, expparams)

# Plot the posterior.

updater.plot_posterior_marginal()

# Add a legend and show the final plot.

plt.legend(['Prior', 'Posterior'])

plt.show()

(Source code, svg, pdf, hires.png, png)

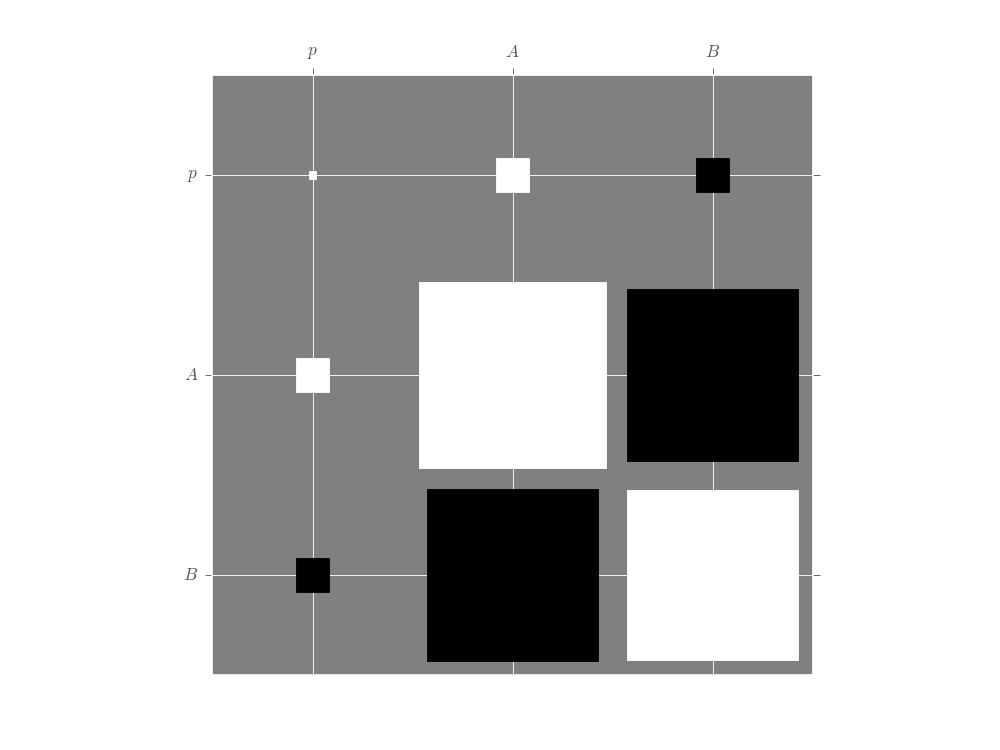

For multi-parameter models, the plot_covariance()

method plots the covariance matrix for the current posterior

as a Hinton diagram.

That is, positive elements are shown as white squares, while negative elements

are shown as black squares. The relative sizes of each square indicate the

magnitude, making it easy to quickly identify correlations that impact estimator

performance. In the example below, we use the Simple Estimation Functions to

quickly analyze Randomized Benchmarking data and show the resulting correlation

between the \(p\), \(A\) and \(B\) parameters. For more detail,

please see the randomized benchmarking example.

p = 0.995

A = 0.5

B = 0.5

ms = np.linspace(1, 800, 201).astype(int)

signal = A * p ** ms + B

n_shots = 25

counts = np.random.binomial(p=signal, n=n_shots)

data = np.column_stack([counts, ms, n_shots * np.ones_like(counts)])

mean, cov, extra = simple_est_rb(data, return_all=True, n_particles=12000, p_min=0.8)

extra['updater'].plot_covariance()

plt.show()

(Source code, svg, pdf, hires.png, png)

Advanced Usage¶

Custom Resamplers¶

By default, SMCUpdater uses the Liu and West resampling algorithm [LW01]

with \(a = 0.98\). The resampling behavior can be controlled, however, by

passing resampler objects to SMCUpdater. For instance, if one wants to

create an updater with \(a = 0.9\) as was suggested by [WGFC13a]:

>>> from qinfer import LiuWestResampler

>>> updater = SMCUpdater(model, 1000, prior, resampler=LiuWestResampler(0.9))

This causes the resampling procedure to more aggressively approximate the posterior as a Gaussian distribution, and can allow for a much smaller number of particles to be used when the Gaussian approximation is accurate. For multimodal problems, it can make sense to relax the requirement that the resampler preserve the mean and covariance, and to instead allow the resampler to increase the uncertianty. For instance, the modified Liu-West resampler \(a = 1\) and \(h = 0.005\) can accurately find exactly degenrate peaks in precession models [Gra15].

Posterior Credible Regions¶

Posterior credible regions can be found by using the

est_credible_region() method. This method returns a set of

points \(\{\vec{x}_i'\}\) such that the sum \(\sum_i w_i'\) of the

corresponding weights \(\{w_i'\}\) is at least a specified ratio of the

total weight.

This does not admit a very compact description, however, such that it is useful to find region estimators \(\hat{X}\) containing all of the particles describing a credible region, as above.

The region_est_hull() method does this by finding a convex

hull of the credible particles, while region_est_ellipsoid()

finds the minimum-volume enclosing ellipse (MVEE) of the convex hull region

estimator.

The derivation of these estimators, as well as a detailed discussion of their performances, can be found in [GFWC12] and [Fer14].

Online Bayesian Cramer-Rao Bound Estimation¶

TODO

Model Selection with Bayes Factors¶

When considering which of two models \(A\) or \(B\) best explains a

data record \(D\), the normalizations of SMC updates of the posterior

conditoned on each provide the probabilities \(\Pr(D | A)\) and

\(\Pr(D | B)\). The normalization records can be obtained from the

normalization_record properties of each. As the

probabilities of any individual data record quickly reach zero, however, it

becomes numerically unstable to consider these probabilities directly. Instead,

the property log_total_likelihood records the quantity

for \(M \in \{A, B\}\). This is related to the Bayes factor \(f\) by

As discussed in [WGFC13b], the Bayes factor tells which of the two models under consideration is to be preferred as an explanation for the observed data.